[ad_1]

Egypt is a vacationer vacation spot well-known for its archaeological websites, pure magnificence and historical tradition. However fascination may be discovered even in additional mundane locations, as in an uncommon type of wall artwork ubiquitous in Egyptian residences and small companies.

Not fairly pictures, the posters are photoshopped representations of quite a few pure environments or differing architectural kinds, juxtaposed in inconceivable methods. These made-in-Egypt mandhar ṭabīɛī, or “pure landscapes” – which vary in measurement from small, 50-by-35 cm framed photographs to wallpaper-scaled – reveal a very Egyptian type of exoticism.

All of the posters illustrating this text come from my 2009 fieldwork in Cairo, bought for just some Egyptian kilos (lower than $US1). These idealised photographs are displayed throughout the nation, in non-public indoor areas, espresso retailers, eating places, hairdressers, and rural and concrete areas, however are particularly widespread within the arid Sinai countryside, Libyan desert and west Mediterranean coast.

A lighthouse borrowed from Scandinavia enhances this 2009 poster.

The posters depict a model of the “unique” not centred on unusual date palms, flat fields or mundane sand dunes – all clichés utilized in vacationer catalogues to draw guests to Egypt. As an alternative, they specific a extra native aesthetic kind, far faraway from Western requirements.

Nature’s Photoshop artisans

I at first incorrectly assumed that these posters had been low-cost Chinese language merchandise filling a distinct segment Egyptian market. In truth, they’re designed and produced within the Shubra neighbourhood of Cairo or the close by suburbs. Maktaba al-Maḥaba, a serious Coptic Christian bookstore (مكتبة المحبة القبطية), distributes their catalogues throughout Egypt (and apparently all through the North Africa area, as I’ve since seen some posters in Tunisia’s Jerid oasis and the Moroccan Rif).

The primary design software in these Egyptian cut-and-paste compositions is clearly Photoshop (or an analogous software program). The craftsmen present nice mastery of pasting, fusion, blurring, cropping, scaling, duplication and different strategies, creating on their pc screens three-dimensional scenes encompassing all the perfect of various continents – even when it means implausible coexistences and real issues with scale.

Although people are uncommon in these posters, right here we see the recognized Copt saint Tamav Irene (1936-2006) and the Pope Pope Cyril VI (1902-1971).

The artisans of the Maktaba al-Maḥaba shoppe, who don’t hesitate to cater to the Christian neighborhood by printing Jesus Christ or the late Pope Shenouda III in these bucolic settings, undoubtedly inherited the Coptic iconographic know-how behind the shop’s infinite manufacturing of pious photographs depicting triumphant saints, benevolent popes and monks, and struggling martyrs.

Snow, rainforests, Christs and Chinese language pagodas

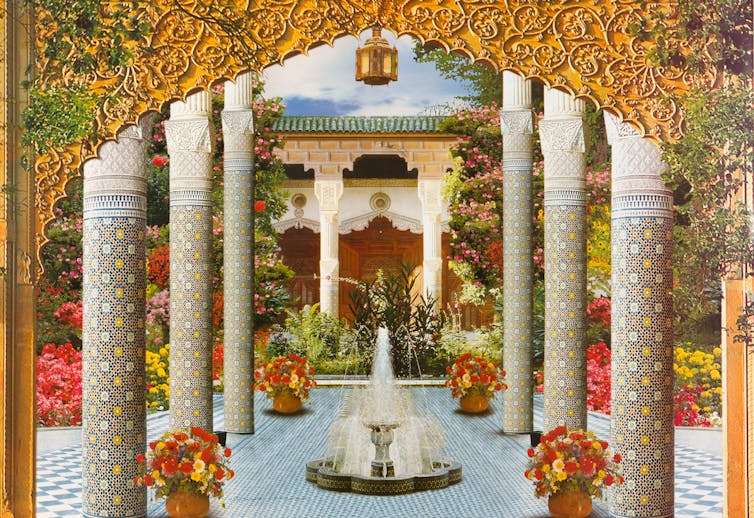

Water is in every single place in these posters, its presence seemingly required by customers. It might be a sea, a lake, a river (typically with fanciful route), or, in fact, these elaborate fountains.

The opposite prerequisite is greenery and a wealthy palette of florals – regardless, once more, of botanical, agronomic or ecological incongruities and impossibilities. The posters are saturated with backyard motifs, leaving some house for the sky however little or no room for people or animals.

Architectural components mirror not simply Islamic motifs (columns, ceramics) but in addition kinds fairly overseas to Egypt, equivalent to Californian villas, Chinese language pagodas and Scandinavian lighthouses. Different unique landscapes embrace copy images of snowy Swiss mountains with equatorial rainforest waterfalls, punctuated by the palace of Versailles or different Renaissance-style constructing, plus Islamic ponds with lush floral preparations – and maybe a yacht or ice floe within the background.

Generally, there’s a photographic enlargement of an English backyard in its autumn glory. However, usually, pure nature isn’t sufficient, and the thirst for exoticism triumphs.

What’s exoticism? What’s ‘pure’?

These posters are prominently displayed throughout Egypt, providing visible enjoyment of fuel stations and native eateries. In Siwa, a distant oasis within the Libyan desert of Egypt, I noticed them within the marbūɛa (front room) of homes.

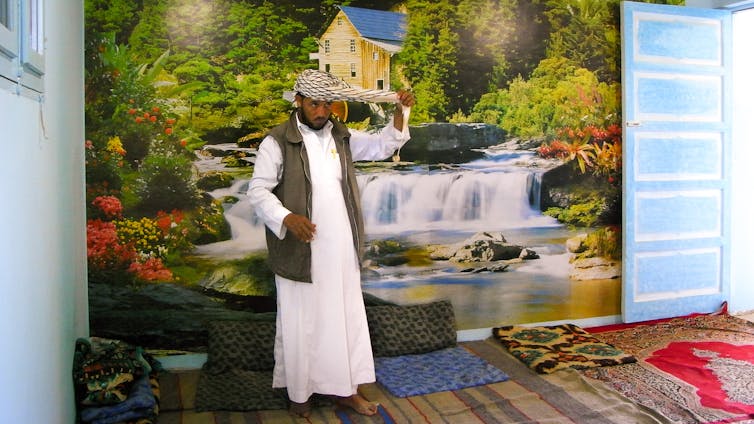

The lounge inside in a newly constructed residence within the Siwa Oasis of Egypt’s Libyan Desert.

Siwa inhabitants don’t see their panorama as significantly unique or fascinating. In the meantime, vacationers who come to Siwa don’t give attention to the world’s true agro-ecosystem however look past at a extra acquainted scene, the “already recognized” oasis of their Western imagery, an iconic Eden panorama that conforms with their very own notion of exoticism.

This remark helps social anthropologist Gérard Lenclud, who mentioned that panorama is:

“the product of the view of somebody who’s ‘foreigner’ to it. Man doesn’t consider elaborating a landscaped illustration of the place to which he’s connected and the place he works or lives.”

Unique is at all times discovered elsewhere, past the horizon.

Fountains are recurrent components of Egyptian posters.

What does this reveal about Egyptians’ supreme of nature? In accumulating photographs from different eras and locations, these posters create an unique house situated someplace between the nostalgia for a misplaced Eden and the promise of Paradise. The inclusion of Islamic golden-age gardens, Swiss chalets and Atlantic lighthouses additionally reveals the attractiveness of a globalised world.

The amassing of components speaks for itself: saturation might be the important thing idea of common aesthetics, a part of the pursuit of sensorial expertise. The beholders of those mandhar ṭabīɛī constructions don’t distinguish between “pure” nature and synthetic renditions. In interviews I discovered that Siwa residents both don’t discover this phoney flavour or don’t care about its inauthenticity.

Desires of lush gardens

What Egyptian customers do clearly choose is that the posters’ iconic jumble needs to be organised in accordance with repeating patterns of three predominant components: flora, water, and structure. A few of these components reappear from poster to poster – the identical fountain may be recognised stretched a bit right here, or with a unique basin there.

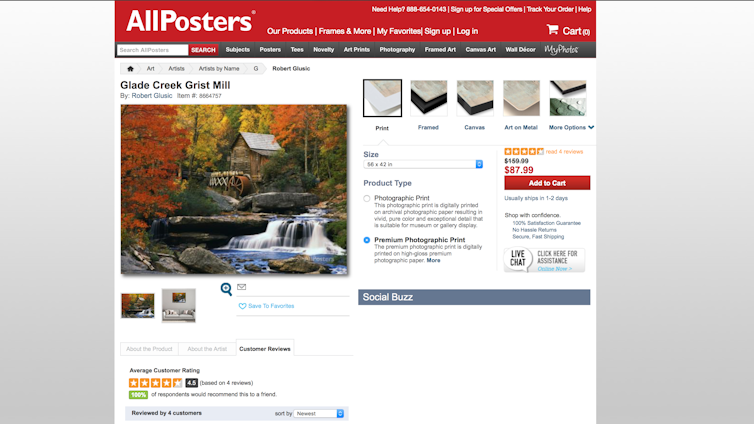

I might unwittingly observe the biography of some key patterns as I vainly sought proof of an analogous craft around the globe. The mill typically seen within the midst of a lush tropical vegetation, for instance, is “sampled” from a poster entitled “Glade Creek Grist Mill, Babcock State Park, West Virginia” (credited to Robert Glusic). The unique is an already romanticised depiction of a vacationer attraction in Babcock State Park in West Virginia, United States.

This West Virginia waterfall is sampled in some Egyptian posters, together with the one within the Siwa residence, proven above.

In Egypt, a easy copy of this picture doesn’t suffice. That distinguishes its common aesthetic custom from Europe’s, the place, in accordance with Jean-Claude Chamboredon within the collective ebook, Defending Nature: historical past and beliefs, “the countryside as an idyllic social setting outcomes from an extended technique of progressive disappearance of the agricultural proletariat … for the reason that second half of the nineteenth century”.

The French countryside has turn out to be a perfect, impartial house whose very building (through a historical past of social struggles) is erased and changed with a story of an genuine, conventional and exquisite seasonally-changing topic. (I recall now the plywood-mounted poster of a continental forest that my dad and mom proudly displayed in our front room in Le Havre, France.)

Not so in North Africa and Egypt. In deserts, it appears, the folks dream of lush gardens and Italianate palaces that enable them to be swept away, if just for a second, from arid native soil.

[ad_2]